Farming and its others, and other ways of farming

Why so many farmers are raging against the conditions of food production, and what other farmers we should look to for alternatives

Common Ecologies1

1. This text was written by Manuela Zechner, Lea Loretta Zentgraf and Bue Rübner Hansen of the Earthcare strand of Common Ecologies, inspired by our event : “Farmers protests: where do we stand?” (February 2024, video here). Quotes by farmers and collectives are taken from this event.

Agriculture is in crisis, and so are representations of agriculture. Farmers have always been multitudes, and to escape the deadly treadmill of industrial agriculture, we need to recognize this now more than ever. In this text, we develop a map of the current crisis outlining the class, gender, race and ecological composition of agriculture, and the power relations, political games, and affects at play in it. Our text, based on notes from conversations with allies in European agroecology, peasant and agri-syndicalist movements, moves from an analysis of actors to one of alliances.

Farmers are multitudes

The contradictions that characterise industrial agriculture are reaching unprecedented levels, with struggles erupting at various levels. Recent European farmers’ protests have left us equal parts inspired and baffled, as spot-on slogans like ‘no farmers, no food, no future’, mix with racist and anti-ecological sentiments. The grievances and demands of organised farmers did not just emerge yesterday, but these days they are instrumentalized and enacted in a very particular way, in a strange game of call-and-response that seems to primarily unfold between the far right, neoliberals, and disgruntled farmers.

Conventional farmers are raging, but not against the deeper structural problems of capitalist agriculture represented by supermarket oligopolies, cutthroat competition, deepening dependency on subsidies and expensive external inputs (pesticides, fertilisers, seeds, fuels, machines, etc.), and skyrocketing indebtedness – not to speak of failing harvests and crop failures. Meanwhile, far-right, neoliberal, and conservative parties use protesting farmers to fuel a sequence of attacks on the often unrecognised actors who make agriculture possible today and in the future: migrant farm workers, women in agriculture, and the non-human species and ecosystems meant to be protected by environmental regulation.

This text focuses on actors on both sides of this divide set up by capitalist agriculture. It zooms in on the many “othered” farmers and others of farming who fulfil key roles in making agriculture just and sustainable but who we don’t see represented in recent protests. At the same time, we look at what it might take to get “conventional” farmers out of the agri-industrial treadmill. Playing with the question “what’s a farmer?”, learning from our allies and dancing to the many meanings and agents of farming, we share these notes on farmers as multitudes. The first part of this text will look at the agents and the second part will map the alliances that can get us out of the crisis in agriculture.

While Europe still has many peasants, and plenty of migrant, landless farmers, those protesting in recent months were mostly entrepreneurial and capitalist farmers. These different fractions follow different strategies of life, and their interests and identities are often in tension. Whereas peasant farmers produce mostly for local markets and self-consumption and mostly depend on the labour and nutrients available at their farm, entrepreneurial and capitalist farmers are locked into very long chains of competition, dependence, exploitation and extraction. Migrant farmers struggle to make a living, and sustain families or friends abroad, often with intimate knowledge of agro-ecological methods from their home territories, but without access to land and rights.

When someone says farmer”, most Europeans likely think of a white man on a tractor, and this is exactly the kind of image the media showed us during the farmers’ protests. That’s because of the very patriarchal and often xenophobic ways in which “family farming” has historically evolved in Europe, as elsewhere, with autochthonous men in the driver’s seat taking centre stage, while all others kept out of the picture. But while there isn’t just one kind of farmer – neither in terms of gender, nor indeed race or class – it’s in the interests of some to keep the stereotype alive.

1. Actors

The tragic figure of the industrial farmer

Industrial farmers are contradictory, sometimes tragic, figures. They are under economic pressures that hollow out their livelihoods, yet tow the same line as the political parties, banks, and agri-conglomerates that profit from their economic suffering. They see climate change and soil degradation undermine their livelihoods, but oppose all the coordinated measures to end those processes. They are dependent on public subsidies but attack public regulations. And some of them, under influence of conservative and far-right ideologies, rage against women, while they struggle to find wives, and against migrants, while migrant workers keep them in business. Contemporary industrial farmers are stuck in a brutal game in which they have very limited chances of success.

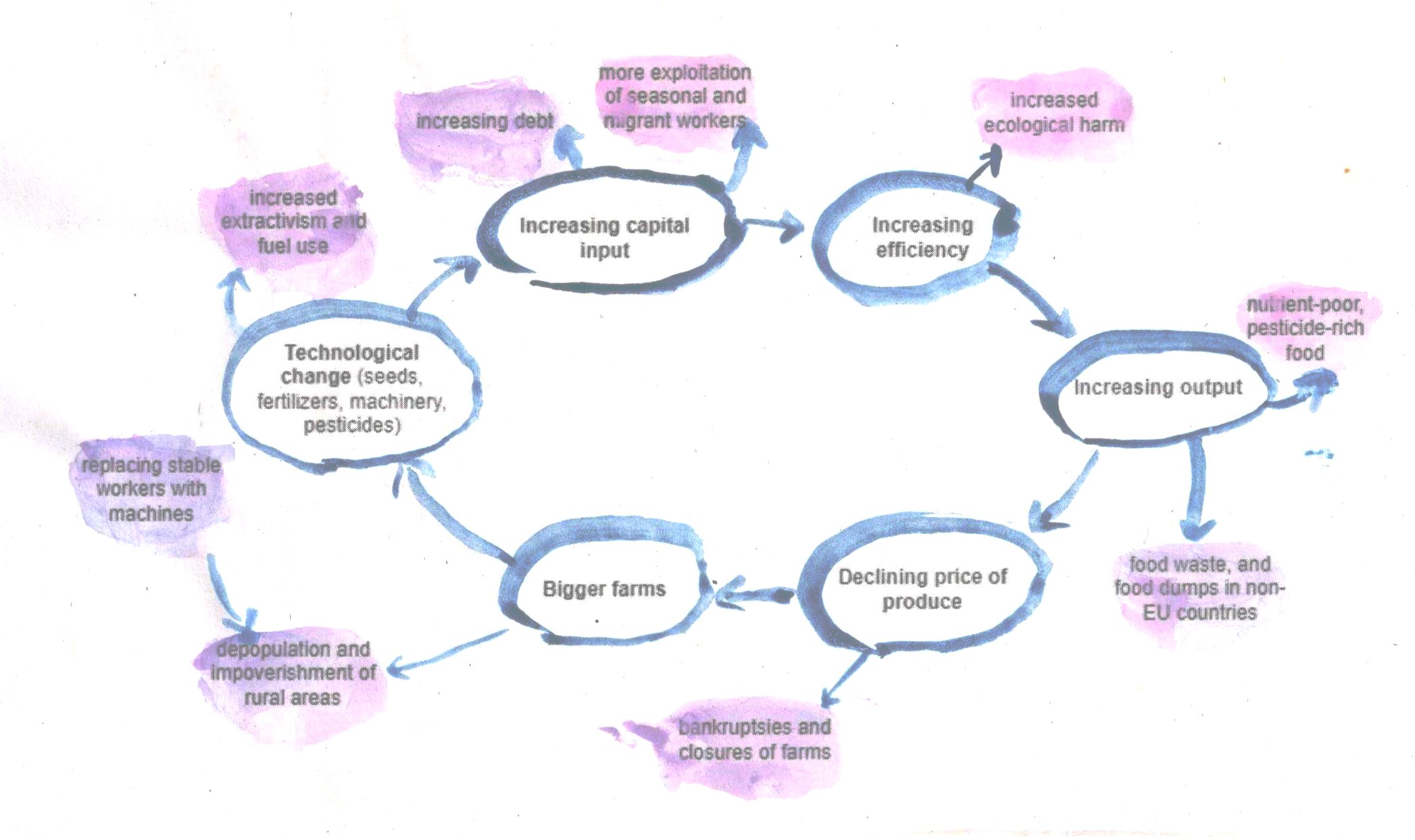

That so many farmers are frustrated and angry should be no surprise: whereas big capitalist agri-conglomerates and large landowners rake in profits and subsidies, most conventional farmers are caught in the so-called treadmill of agriculture. This concept describes the vicious circle of competition, which forces farmers to invest in new technologies and economies of scale, often through loans. The productivity gains of this lead to profits for some, but overall they result in falling food prices due to increased supply. This creates renewed pressure for more acquisitions and investments. At the same time, price pressure from oligopolistic supermarket chains means that farmers get paid very little for their crops, even when they are sold at a premium in supermarkets. As a result, most of those farmers are deeply indebted and dependent on subsidies, and under strict pressures to maximise yields, no matter the negative consequences.

The treadmill of agriculture also has major ecological consequences. Conventional industrial farms compete on size: the big machines only work on large monocultural fields where the same few crops are grown. This system kills the microorganisms, fungi and worms that keep the soil fertile and loose. And dead soil requires more fertilisers, toxins and ploughing than living topsoil. Ultimately, the soil is treated as a dead substrate. Because the soil is ruined and lacking organic life and matter, it loses its capacity to hold water. This increases the risk of both drought and floods, as well as toxic spills and seepage of pesticides and nutrients into groundwater and streams.

The overall picture is depressing. Monoculture landscapes are ecological deserts. Pollinator populations are rapidly declining. Water bodies suffer from eutrophication, suffocating the species that used to live there. On land, many farmers suffer from a poor quality of life, stress, depression, and toxicity. For example, a survey from the Danish agri-industry body, Efficient Agriculture, found that “95 percent of farmers who leave the industry experience an improved quality of life”. In France, a farmer or farm worker commits suicide every day – a suicide rate 43% higher than the rest of the population. Look up farm decline rates in your country and you’ll likely want to cry.

2. As Ernst van den Ende of University of Wageningen proudly envisions in his narrative of a fourth green revolution, in this interesting Arte documentary (at 32’) https://www.arte.tv/en/videos/098069-001-A/europe-at-a-crossroads/

The peasantry that never went away

Recent farmers’ protests are far from the first or most powerful in history – indeed farmers’ insurrections, or peasant revolts, have occurred throughout the history of class societies. Those were always class struggles, cut along different lines, where subaltern farmers fought feudal lords, capitalist landlords, tax authorities or the church, or where farm workers fought their employers. In the face of global capitalist agribusiness, peasant farmers have long been organised into massive global movements such as La Via Campesina. For decades those have called out agribusiness, run campaigns against social and ecological devastation, drawn up policy proposals and built grassroots power, regionally and across all continents. La Via Campesina builds on popular peasant feminism, on struggles for the rights of landless as well as land-holding farmers, on migrant and seasonal agricultural workers, and on respect for the earth. They reject the morbid game of playing the past against the future, of feudal systems being given modern gloss, and resist the techocapitalist bid to remove farmers’ autonomy.

In recent European farmers’ protests, we’ve seen large and industry-inclined interest organisations emerge as protagonists driven by large land-owning and agri-corporate actors that refuse to imagine food production beyond the treadmill of agriculture. Why? Because the treadmill is their business model.

But did you know that European peasant and agroecological farmers have also been amongst the recent protests? They refuse to be cut out of the picture, or pitted against their friends, neighbours or classmates who went down the industrial route. They, however, haven’t received nearly as much attention, and in the worst instances they are treated as a dwindling population of hippies and holdovers from a moribound past.

Yet small landholders still make up the vast majority of farmers in Europe. Most land has now accumulated in the hands of industrial farmers, but most of the people in farming are doing smaller-scale, peasant-type farming. And globally, peasants are the greatest contributors to feeding the world. They do so in ways that are much more compatible with sustainability –plenty of good reasons to hold off with the idea that peasant agriculture is a thing of the past.

Peasant agriculture innovated incessantly, not just because it adapts to a multitude of factors and events in real-time and with relational and generational intelligence, but also because it works smartly with technology. That means to balance dependencies, costs, damages and energies against usefulness and autonomy gained –critical of corporate tech narratives. Necropolitical modernizers dream of reducing farmers down to a few precarious greenhouse technicians and reducing nature down to a series of techno-chemical variables, banking on ecologically, socially, and economically unhinged fantasies of fully automated farming – farming without farmers.2

Our argument goes the other way. Farmers are multitudes, and it’s time to rally behind them, ally with them, and become part of them. But it’s not just peasants we should look to when we look for paths to sustainable farming. In the section that follows, we honour the very significant “others” who sustain agriculture, whether they are land-owning or landless ‘farmers’: women farmers, migrant and seasonal farmers, more-than-human collaborating species like pollinators, soil critters, fungi, plants, grazing and shitting animals, and associated others, as well as our common ecologies of water, air, ground and so on. All those are indeed agents of farming, and not just in a minor role. Farming is a field of lively, rebellious and resilient multitudes, and it’s in looking to these that we may begin to see ways out of the ecocidal, exploitative circle of industrial agriculture.

Women farmers

“Well guess who milked the cows while the men were out protesting!”

Woman farmer in Germany, speaking of the 2024 protests

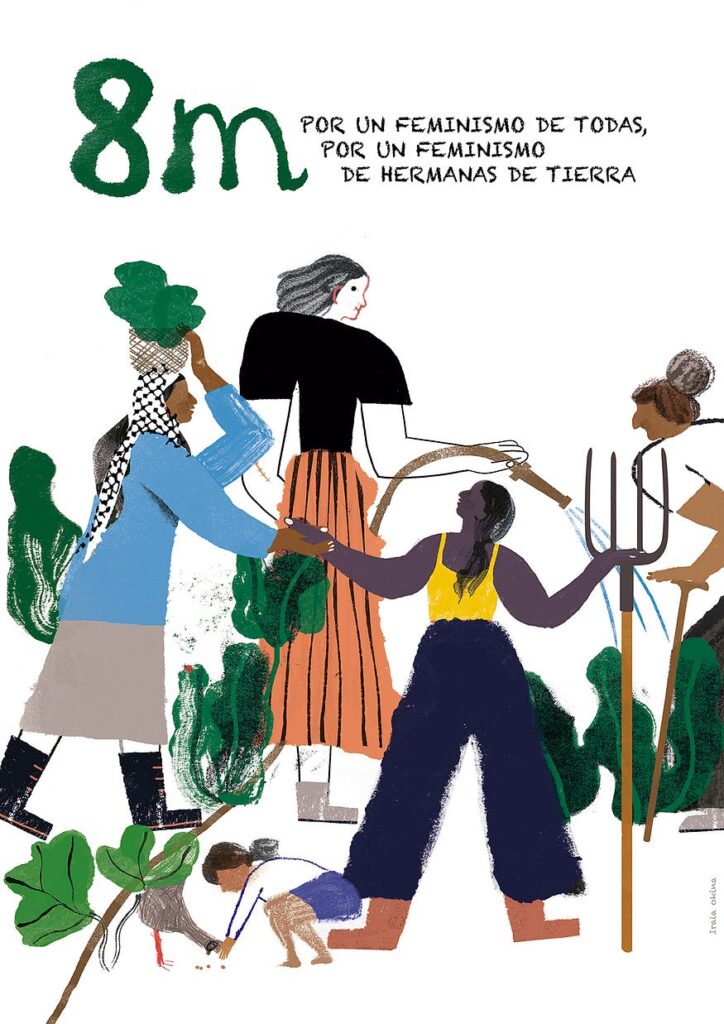

On 8th March 2024, amid farmers’ protests in Europe, Spanish feminists published a call: “For a feminism of sisters of the earth”. They wrote: “Sisters of the land, these are turbulent times, with tractor protests on the roads. Sectors of the countryside have taken to the streets. These protests rebel against the urban, paternalistic, condescending perspective of the countryside. A perspective and way of talking about us that pigeon-holes us as one type of countryside and one story. Of course, we know the real interests behind this communication strategy and the confusion it generates is a real concern. What are they demanding? Who’s doing it? Who can do it? From what positions?”

There is a long patriarchal hangover in farming, written into laws and social security regulations that have for centuries reduced women to dependents, housekeepers, helpers of their farmer husbands, or indeed male relatives or employers. Women long had little to no social rights as compared to men in farming. In Austria, for instance, women farmers only gained the right to their own pensions in 1992. In France, women farmers only obtained their own social security status in 1980, and it took longer still for full pensions and other social rights. Similar timelines apply to other European countries, and there are plenty of policy reports to attest that women are still discriminated against, underrecognized, undervalued and underrepresented in farming today.

The feminist struggles of women farmers have been significant and led them to more equal rights, but farming remains biassed towards men. That’s still also due to cultural factors – men inherit a majority of farms, and thus represent the vast majority of landholders in European farms. When they own farms, women tend to own smaller holdings than men and focus more on diversification activities that can be combined with care work. That leaves them at disadvantage when it comes to agri-subsidies, even though care and diversity are altogether more beneficial than specialisation and large-scale monocultures to both people and ecosystems.

During the speeches at the national farmers’ protest on January 15, 2024, in Berlin, only two out of 10 people speaking at the podium were women. A fair proportion if you go by the amount of land women hold; yet not so fair if you go by the number of women living and working on farms. What counts, for gaining representation at such an event, is your capital – since land and capital correspond to each other in industrial farming.

They spoke more briefly than the many men of the major farming associations. None of the two women speakers mentioned gender inequalities and the structural problems women encounter in patriarchal agriculture in Germany. But they did speak of the need for democratic protest and for taking a clear position against the far-right, populist forces working to co-opt the movement. Breaking the glass ceiling – or “grass ceiling”, as it is called in agriculture – is certainly a little step away from some toxic masculinities and associated fantasies of dominating nature, maybe even alongside subordinate human others.

Yet the grass ceiling of those female speakers in Berlin is not the same as that of the many women with less access to education, land and capital. And for many women farmers, it’s less of a question of ceilings than it is of fences. The two women on stage did not mention their sisters in seasonal agricultural work – the many migrant, seasonal and day labourers working Europe’s fields and farms (who they even might be employing, and exploiting, at their very own farms). To put it bluntly, they play into pinkwashing the image of the farmer as a successful agri-capitalist, but they don’t help question the treadmill and its exploitation. A story we’ve seen before, in the episode on entrepreneurial feminism, of that great period drama called “neoliberal capture”.

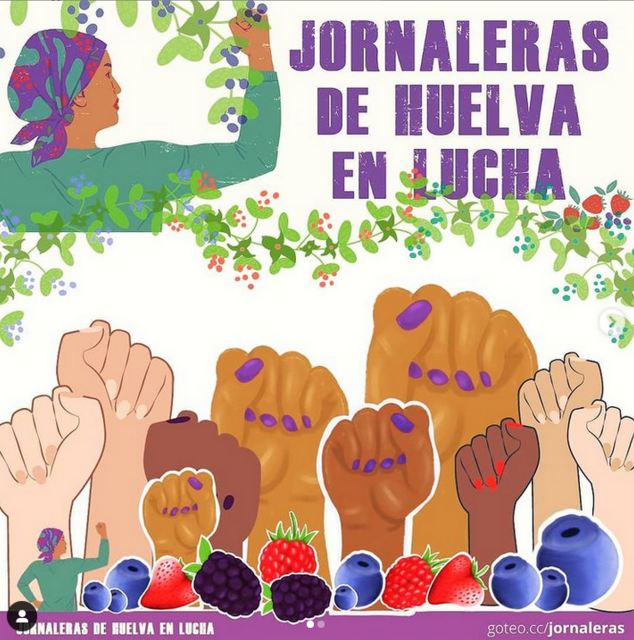

The Jornaleras de Huelva en Lucha is a feminist anti-racist syndicalist syndicate fighting the exploitation of women and migrants picking berries in the Spanish Almería heartlands of polytunnel agriculture. They do not speak of glass or grass ceilings, but of borders, fences and the systematic violation of rights. Such as the fact that hundreds of migrant workers in Almería live in dismal shacks: “They’re not talking about that in the protests and tractor blockades either”. The Jornaleras, like many similar migrant farmworkers campaigns, demand much more than a pay rise – they fight against toxic agroindustry, for the right to water, lively rural communities and global solidarity.

We see a lack of representation in these protests, we keep seeing tractors. We keep seeing people on the streets which are mostly men, mostly white men, this is not really representing who is working in the Spanish countryside. So of course there is a huge amount of women working in the countryside who used to be invisibilized. And there are a lot of daily labourers and a huge part of them are migrants and we don’t see migrants on the streets and this is a critique we have.

Nos Plantamos (ES) and Ecologistas en Acción (ES)

For us the problem is not the policy of environmental measures – we consider them necessary – the problem is the costs of doing so to be assumed solely by the sector which is already suffering. We really think that policy should support this really necessary transition.

The population of agricultural workers is increasing a lot and is becoming more important. There are more people working in the lands and in the fields that do not own the land. This is not reflected in the protests. And is also not taken into account by the government responses. That is a big issue and something we are working on. To fight against this union imbalance and to advocate for stronger agricultural workers unions to support their rights. […] More broadly which is also often overlooked and we are trying to work on with the associations is to make some connection with farmers from the South. There is also this imbalance that French and European agriculture rely a lot in terms of fuel, energy, chemicals, it relies on an extractivists agriculture. It is a colonial agriculture.

Association A4 (FR)

Seasonal workers, landless farmers

“What we’re seeing is a farmholder movement that brackets all the landless farmers sustaining agriculture”

Activists from an anti-racist agricultural and artisanal association in France

Without landless and mobile farmers, agricultural production would be in dire straits, and food prices would skyrocket, as we see in post-Brexit Britain and during the pandemic. The workforce on fruit and vegetable farms in Europe is by now largely migrant. They plant, prune and harvest the majority of fruit and vegetables in Europe which is very labour-intensive, heavy work, concentrated over short periods. These farmers don’t hold land or determine what is produced or how, and so no one considers them when we think about agriculture and especially political decision-making over agrarian regulations. They are the most exploited, precarious, exposed (to toxicity, racism, sexism) and invisibilized workforce – and precisely as such they are indispensable. Following the provocation of Association A4 above, we call them farmers here: landless, often hyper exploited and rotating between farms, but nonetheless farmers.

This struggle for more organisation and visibility of migrant workers in farming goes far back, to organisations such as the United Farm Workers in the US 1960s, through to contemporary campaigns such as Sezonieri (AT), Jornaleras de Huelva en Lucha (ES), Codetras (FR) as well as many others. During the Covid-19 pandemic, these workers became a rare subject of debate, precisely because their labour became scarce as travel restrictions and social distancing stopped many workers from crossing borders to harvest asparagus and strawberries. However, even after this moment made their importance clear, there has been little or no improvement in their conditions.

Source: Campaigns from Sezioneri and Codetras for migrant land worker’s rights

A key reason for the invisibility of migrant seasonal farmers is the precarity and irregularity of the work and life situations. In many countries, agriculture is the sector with the highest rate of irregularity of employment, that’s to say of people working without proper contracts; for instance, in 2018, 24.2 percent of the Italian agricultural workforce was irregular. This structure of exploitation renders workers highly vulnerable to blackmail, unable to claim rights or pay, barely represented by unions or other organisations. Left to fend for themselves, exposed to wage theft, at risk of sudden loss of jobs and working permits, detention and deportation and facing racism and linguistic barriers, migrant workers can’t easily take to the streets and make their voices heard.

Their structural oppression excludes them from participation in farmers’ protests, as much as the racist classism of agribusiness and mainstream media does. Yet we know of agri-bosses sending their seasonal workers to the protests in southern Spain to add bodies to the protests that defend their employers interests. A double irony and symptom of the corruption and lingering colonialism in agriculture. Agribusiness and its various entities know very well that they need migrant workers, but need them as precarious and othered, that is as exploitable. For them, anti-immigrant sentiment and racism are not bugs, but aspects of their business model.

More-than-human collaborators

“We are nature defending itself”

A multitude

Alongside all those fighting for a socially and ecologically just future, we must reject “the myth of the organic unity of the farming world”. As Soulèvements de la Terre put it, we must refuse the polarisation some people create “between urban and rural dwellers, environmentalists and farmers, both settled and new”. Ecology will be peasant and popular, or it won’t be – and we are indeed nature defending itself here.

The white patriarchal industrial story of farming is one of domesticating nature, of landscapes cleansed of any species except those that enter into the final commodity: monocrops and animals bred into creatures much different than even the domestic animals of 100 years ago, and kept on fields and in barns of monstrous size. It is a story that justifies ecocide in the name of efficiency and tonnages of crops, eggs, milk, and meat. It’s a story that exploits some species, and ignores and kills most of the symbionts that make for healthy ecosystems: the pollinators of the crops, and the predators of pests, as well as the worms, fungi, insects and microorganisms that make for healthy soil.

The effects of this process are widely known: climate and biodiversity crises are perhaps the most known amongst the nine planetary boundaries we are about to burst, and industrial agriculture is a key driver of them. Extractivist-industrialist ways of relating to soils, plants and animals undermine life both socially and ecologically. Big farms create perfect conditions for viral and bacterial transmission and evolution. As sites where human and animal labour are completely subordinate to capital, big farms make big flu.

But climate, biodiversity and pandemic crises are not just products of agriculture: they put agriculture itself in crisis through droughts and floods, pollinator loss and sick and furloughed workers. More directly than other forms of production, farming has to do with our interdependencies with nature, or rather as a part of it. This is where in the chain of agri-exploitation, another set of “others” enters the scene: animals, plants, fungi, critters, self-organised into relations of conviviality, side-by-side and overlapping, producing the planetary ecosystem called the biosphere. Ideas and practices of modernization always worked to cast those as other, different from humans, subordinate and subjugateable, mere resources to be used for human development or – all together – as brute “nature” and “environment”, the other and scene of humankind.

For agriculture to become sustainable and just, it must relearn to think and practise our relations with the living and geological worlds that surround us in terms of mutualisms and partnerships. The ecological sciences teach us what ancient farmers knew through experience and cosmology: that the earth is living and the creatures around each have a part to play. Partnerships with the critters, microbes and fungi that create healthy soil, and with the insects and birds that eat the would-be pests, and with the animals that loosen and fertilise the soil, are all essential for producing food in ways that are good for all in more-than-human worlds.

For domestic animals to become partners in agriculture, rather than a serious source of greenhouse gas emissions, land use and feed consumption, we must reestablish mutualism with them. This requires respecting their dignity and needs. Today, industrial farms are basically death camps where animals are deprived not just of liberty (many were bred to never survive in liberty), but of childhood (male chicks), adulthood (lambs, calves), contact to their mothers (offspring of milk-giving animals), the right to roam or even move altogether (tiny cages), to daylight and species-appropriate social interaction. But domestic animals, living in flocks outside, can help utilise marginal lands, restore ruined lands, and eat our leftovers in exchange for manure and proteins.

The capitalist division between the city and the countryside works perfectly in channelling human love and care to pets whilst keeping farm animals separate and desubjectified, as if they were fundamentally different kinds of animals (operating with notions of species intelligence or subjectivity straight from the playbook of racial eugenics). The notion of giving animals a good life and by that legitimising taking their life does not apply to factory farms. Animals are treated like plants, or worse, static metabolic machines. They’re at the bottom of a chain of desubjectification that also applies to temporary labour, and historically also applied to women. There’s no sustainable and just reinvention of farming without breaking this brutalising logic, nor without taking seriously agriculture’s dependency on and potential partnerships with non-domestic forms of life.

The evolution of the farmers alliance from 2019 poses some questions to the food sovereignty movement and also to the left, probably more generally in Ireland and abroad. What have they done? They have basically turned from a grass-roots movement into a political organisation, they have also moved beyond the issues from food and agriculture to capture quite explicitly other rural grievances and discontempts to absorb them into their platform. They also draw on some of the food sovereignty discourses, they are clearly reactionary as they defend the family. They are anti-transgender, defending private property, they have an exclusive idea of national sovereignty. The questions I want to pose are: What would a progressive version of the farmers alliance look like? How would it differentiate itself from farmers’ alliance? Who would it form alliance with in Ireland and internationally? […] The need to expand communicative power and the idea of extending relations beyond the food and land justice movements and how that links to movements around housing, around costs of living, pro-Palestinian movements…

Root and Branch Collective (IR/UK)

Agri-ecological multitudes

Beyond the Global North, there is much awareness of the fragile balance we’re risking to undo in our interdependence within ecosystems. Agroecological and peasant farmers, Indigenous movements, ecofeminists and radical environmentalists have contested anthropocentric agriculture for a long time. And even in Europe, more and more are aware that addressing climate and biodiversity crises is in their individual, class and species interests too (for those unable to think beyond interest and imagine farming as earthcare, this is a way to think about it). These farmers see the importance of environmental regulations, they just demand fair and effective ones.

Even under the pressure to maximise yields, farmers must be attentive to ecological dynamics. Peasants have always, as John Berger pointed out, needed to be closer to seasonal and life and weather cycles, to the health of soils, plants and animals (including humans), to water and sunlight and temperatures, than any other labouring humans. On industrial farms this need persists even as the path dependency of machinery and the pressures of debt and competition make it harder to respect this need. Increasingly, it is experienced as an unwanted dependency and blockage on efficiency and planning.

Accordingly, the great modernising missionaries of the Green Revolution strive to break agriculture’s dependency on seasonal and ecological circles. Industrial agriculture remains dependent on earthcare labour and the activity of manifold species, but continually strives to make itself independent from both ecology and workers. This striving only deepens their dependency on the treadmill and accelerates its spinning.

How may we break this juggernaut and its destruction of human and more-than-human life? How may we slow down its desertification of the countryside and its relentless capture of farmers’ hearts and minds? The key is to articulate the struggles of agricultural labour and ecology, with those parts of farmers’ interest that remain attuned to the manifold interdependencies of life as well as the harm of indebtedness and endless competition. But such uneasy alliances are hard to forge as long as farming is seen – and the conditions of farming unseen – through the rosy spectacles of national romantics and the cynical manipulations of agribusiness.

Who is afraid of the invisibilized others of farming?

The question may sound rhetorical, but it’s real: Who is disturbed by these other, equally real human subjects of farming – seasonal migrant workers, women and young farm labourers, undocumented agricultural workforce? What does their labour, their bodies, their presence, their future visions, their vital importance signify, that we – the supposedly homogeneous majority public of European media and politics – cannot hear? And who is afraid of taking the more-than-human collaborators of farming seriously? The answer is, of course, not just cultural but very much also economic and political.

One part of what makes us unable to see farming for what it is today, and move on from there, has to do with the romanticised image of farming as a family activity, small scale and autochthonous, and with the nationalist idealisation of the farmer. Let’s be clear: small-scale, peasant, agroecological farming is amazing and needs to expand, but not by way of national-romantic ideologies or associations. To face the big trouble that farming is presently in, we need to see its real labourers, and its relations of patriarchal, racist, classist, and ecological exploitation and extraction – and make the future of farming an exercise in empowerment and transformation rather than erasure and purification.

The nostalgic image of plucky family farmers sells. It also stokes familiar sympathies without actually questioning the state of farming – news stories of the travails of farmers build their sympathies on the image of troubled family farms. But we need to realise that farming is no longer a proud family economy that feeds the nation – but also that this economy was never the harmonic whole it’s imagined to be, because of how it relied on the exploitation of farm workers, unequal gender relations, and the often unwilling labour of children and elderly people working hard until they die. This unpleasant view on the exploitation of lives and livelihoods is something the political and economic elite knows but cannot let people see, as it will make everyone furious.

Some can’t face this because they want a return to the pater familias and blood and soil –- those are probably not the majority, but they cleverly used farmer protests to amplify their views. Of the domination of man over nature, over beasts, over “resources”. Others, because it is deeply disturbing to recognize the loss of a romanticised past and at the same time face the exploitation and destruction that puts food on our tables today – it’s hard to face horror when there seems to be no better way, no path beyond horror.

Global chains of capital and labour exploitation are ugly to look at, and agri-business works hard to make these invisible, at the same time as working to make socio-ecologically just models of farming seem implausible, or indeed to create false imaginaries of technical solutions towards a so-called sustainable agriculture. Yet really what we need to see is that the ongoing farmer’s protests are very much class and labour disputes, as Eva Gelinsky also puts it in a text on the Dutch farmers protests. That doesn’t mean that they can be reduced to labour, but at their core is a struggle over profits, over hegemony, wherein divide and rule is a central tactic.

This is why, as we have argued in “Transforming Agriculture and Beyond”, we need counter-tactics rather than romanticised notions of agroecology, best practices and consumer choice. Where there is an adversary, there is need for tactics and struggle –- and there is no lack of (class, race, gender, species…) enemies to the farming multitudes that sustain our lives. Good tactics and strategies are based on telling real enemies apart from instrumentalized pawns and disgruntled others, and working with that: there’s no lack of challenges when it comes to applying this to farming, but we must work to get there. Which brings us back to the key question of alliances.

In general as analysis and as a strategy, of course there are problems and we need mobilisation. And on the other side it is another symptom of the crisis of mainstream agriculture. (…) We are organising an agroecological conference. This is an attempt of connecting more than 80 organisations, collectives and local agroecological initiatives and peasant struggles. Because we think that agroecology as a practice as many local and territorial initiatives – they are developing quite significantly in the last 10 years in Italy. The power of our agroecological practices and the power of the social imaginary coming from the desire of another relation with the land are not nearly enough. We need more communication power which is the power of intervening in public debate and rearticulating the order of discourse of public debate and we need also more collective organisation putting at the centre the federative input coming from the centrality of the territorial struggles and initiatives.

Mondeggi Bene Comune (IT)

2. Alliances

Escape routes and alliances to dodge vicious cycles

Escape from the vicious cycle of agriculture is hard, but often attempted. A surprising number of European landowning farmers search for an exit by becoming places of agritourism, producing for local markets and cooperative food schemes, or transitioning parts of their land management to publicly financed “ecosystem maintenance services”. Yet, the competitive pressures of agriculture under capitalism are hard to avoid, and many would-be peasants in the organic and agroecological sector end up underpaying and otherwise exploiting their workers. This is why peasant organisations like the MST in Brazil or since recently the AbL in Germany, SALT and the Landworkers Alliance in the UK, show an important part of the way forward by representing or allying with landless and migrant farm workers.

While such alliances between employers and employees may appear contradictory, they express a shared desire to break the treadmill of agriculture. They also hold a strategic insight: if workers’ struggles undermine the large-scale exploitation in industrial agriculture, agroecological food production will be on a more equal footing, and be able to employ people more fairly. Throughout these contradictions and their possible overcomings, the potential for emancipation and a truly sustainable and just transformation of farming lies with the workers.

The agro-industry knows that, which is why it allies with xenophobic forces, setting out to divide (autochthonous) farm managers from (migrant) farm workers, pit them against one another and establish the rule of large farm managers over other types of land-holding and landless farmers. The general invisibilization of migrant labour (agribusiness and capitalist farmers) and its selective visualisation as scarecrow (the far right) are part of the same game: crafting an ‘other’ that problems can be mapped onto. The production of fear, otherness and phobia are key to this crafting, as we’ll explore in more depth below.

Another group of people that also sees migrant labour perfectly well and clearly is the political and administrative class: there is no lack of official statistics on migrant and seasonal work in agriculture, and those statistics leave little doubt as to who actually does the farmwork – even leaving out many undocumented mobile farmers. Were the landless farmers who sustain our agri-food systems taken into account in the political responses that followed the farmers’ protests? Only as externalities.

Neoliberal political representatives were quite happy with the whitewashed image of farming that agribusiness and the far right set up, and the false contradiction they staged. A supposed conflict between a supposedly homogeneous white male class of farmers working to feed the nation, and a mass of foreign workers and products threatening the survival of the same nation, worked well for political response. But migrant workers and racialized people are fighting back, in alliance with other precarious workers, ecological movements and urban activists. Some call for land reparations and restorative justice, fighting for the right of migrants and BIPOC people to the countryside, against the whitewashing of agriculture and the rural. And many defend the labours (and some insist we call it nothing less than work, of a metabolic kind) of all the other species who make life – and agriculture – possible.

We understand the motivations behind the protests, but at the same time it is difficult to be part of the struggles but not being part of the right-wing struggles. But what have the AbL and Young AbL done and achieved? They had a lot of media attention. A lot of new content has been created and alliances as well. The Youth AbL were the first with a statement and positions against the far right. That was why there was a lot of attention, there also was a lot of support from other structures and movements, for example the climate justice movement. The AbL also organised its own demonstrations and spoke up at the protests of the Bauernverband [biggest farmer’s organisation in Germany]. To show that in this kind of analysis they stand together and at the same time to change the discourses of the debates.

Arbeitsgemeinschaft bäuerliche Landwirtschaft (DE)

Against the alignment of neoliberal and neofascist strategies

For decades, the EU has underwritten the treadmill of agriculture through regulations favouring competition and through massive subsidies. The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is one great exercise in holding together the contradictions of this model of agriculture. It strives to maximise yields for the sake of keeping wages low and because great surpluses of food means power within geopolitical competition. At the same time, it strives to keep farming profitable despite the massive decline in prices caused by planned overproduction. Accordingly, subsidy schemes are designed to favour the consolidation of landholdings, privileging large landholders. 80% of the CAP budget goes to larger farms. The CAP is designed by capitalist-industrial agriculture, for industrial agriculture. It is also the reason the EU produces vast surpluses of food, which it has regularly dumped on non-EU countries, putting local farmers out of business.

Recent farmers protests are the symptom of a crisis within the system. It’s a crisis of livelihoods, of rural life, of the EU’s approach to green transition, and indeed of the industrial-chemical system of agriculture itself. Farming is at a breaking point, a critical moment. Crisis can also be an opportunity for change, a moment where past patterns of thought and habit are destabilised, and where past tactics and strategies become ineffective. This makes some people ready to adopt new ways of being and acting, and others cling onto their old ways more aggressively.

Aware of the crisis, the strategists and PR persons of the agro-chemical and agro-technology industries have been preparing for this moment for a long time and had little scruples to do with making the far right their allies and amplifiers. Their affirmation of the white male farmer with a big tractor had probably less to do with proud national sentiment than with profit motives, but they amplified this image nonetheless. Nevermind when a bit of blood and soil ideology gets into the mix, as long as demands are aligned against these “evil environmental regulations”. Nevermind, also, when nationalist outrage about migrant workers and imported produce are not aligned with the highly transnational agenda of the corporate agroindustry. In Germany, radical and populist right-wing parols and statements about the farmers protests circulated on social media and could be found on flags and posters at the protests.

Those enormous contradictions barely produced a little glitch or hiccup, neither with corporate agribusiness nor with the far right. And this is unsurprising. As we know from the history of capital and the far right alike, rarely have a problem with foreigners, migrants and minorities, as long as they can be reduced to humble, non-resistant servitude; in the factories and the mines, in the kitchens and on the fields, in the colonies and the camps.

In recent protests, many large agri-unions acted in synergy with the far right, and the far right jumped on board claiming to represent farmers, sometimes forming new associations such as the far-right Freie Bauern in Germany, or the Farmers Alliance in Ireland. The demands channelled by those actors were primarily to do with stopping environmental regulations and foreign competition, echoing key far-right and conservative talking points (climate denialist, anti-left, nationalist and xenophobic in no minor ways).

This is not just a political but also in part a generational issue. In Germany, the Junge ABL, the youth wing of the farmers association Arbeitsgemeinschaft bäuerliche Landwirtschaft (AbL), ran a very successful social media campaign debunking the right-wing, populist, neoliberal discourses and slogans that often dominated the protests on the streets and in the media and social networks. Their campaign and especially the video with the slogan “YES to peasant protest, NO to right-wing agitation!” went viral and created a different narrative to the farmers’ protests and was presented by a young generation of farmers struggling for access to land, seeds and other resources to create an alternative agri-food system.

Real agents of transformation: the necessary alignments

The farmers’ protests have been dominated by a toxic alliance between those who profit handsomely from contemporary agriculture, and those who are stuck in a perpetual squeeze, and forced to exploit labour, the land and undermine climate and ecosystems to maintain their livelihoods and service their debts. This alliance obscures the real problems in agriculture, and silences and attacks those who have the greatest interest in its transformation.

They are the women, who know that patriarchy is harmful not only to themselves but to the men who have to shoulder excessive pressures. They are the landless peasant workers, whose access to land and justice could re-enliven the countryside, stop the race to the bottom and whose struggles strengthen the relative viability of agroecological production. And they are the land-defenders, ecologists and affected communities, whose fights against agro-ecocide don’t just entail an end to agriculture as we know it, but a whole-scale transition to a model of agriculture aligned with other species and guided by the science of ecology and traditional practices of agriculture. So, consequently, they are the more-than-humans cohabiting places of agroecological farming which foster life and livelihoods of mutualism and conviviality of naturecultures and multitudes instead of monoculture deserts and fields of exploitation and violence against all species.

All these “others” can be protagonists of transformation. But for their common movement to become the face of farming and hegemonize the struggle to transform agriculture, they must align with those who are suffering yet stuck in the vicious circle of capitalist agriculture. Firstly, it must align with the farmers who suffer from this system and are open to ditch the patriarchal, productivist and competitive logics that justify it.

The short-term aim of this alliance is to fight for subsidy schemes and market regulation to be shifted from sustaining and encouraging large-scale industrial farming and supermarket systems with its extreme competition, towards a more ecologically and economically sustainable and more socially planned and cooperative production system. This includes liberalisation and support for peasant markets, peasant- and peasant-consumer cooperatives and transition to agroecological production including retraining, retooling and debt-restructuring.

This will give many farmers who currently struggle to pay workers and treat the land as well as they would like to the chance to do so, and lessen the resistance of the rest to struggles and regulations that aim to force them to do this. The long-term goal of this alliance must be a shift to smaller production units. This will make agriculture more productive per hectare, enable producers to treat each hectare with greater ecological care, and give currently landless peasant workers access to land.

The second and crucial alignment is with the food consumers who are reliant on industrially produced food, and lack access to the healthier and more nutritious food they need. The necessary transformation of agriculture will entail an end to “cheap food”. This cannot be done without massive redistribution that enables urban workers and others to pay more for food: rent controls and wage rises, food subsidies and a narrowing of whole-sellers and supermarkets’ profit margins, or the socialisation of these companies.

Together, such alliances will help us address the drivers not just of the crisis of agriculture, but of the ecosystem crises. They will give the fight for climate justice and ecological sustainability more social depth and rooting, both in the urban working class and in rural areas. And they will help us attack the competitive, exploitative, inequality-driven, and growth-oriented production system we currently live in, and replace it with more democratic, cooperative and ecological ways of producing and reproducing the conditions of life.